Source: Breitbart | VIEW ORIGINAL POST ==>

A color revolution is a catchy term for popular movements that employ riots and street protests to overthrow a government. But behind the scenes, these seemingly organic movements often have a hidden hand.

Organizations and entities fund and foment action under the guise of democratic movements overturning an existing regime through a coup d’état. The origins of color revolutions arguably stem from America’s first modern war, The Civil War, where the Confederacy developed novel irregular operations decades ahead of their time to gain independence from the Union.

In May 1864, Captain Thomas Henry Hines arrived in Canada. He combed Montreal’s saloons and boardinghouses to recruit a small army of commandos to execute covert actions for the Confederate Secret Service based there. As a member of the clandestine organization, the swashbuckling cavalry officer had devised the plan to foment insurrection in the Midwest. The Northwest Conspiracy, as it came to be known, called for an armed uprising by tens of thousands of Copperhead Democrats joined by thousands of Confederate prisoners. Copperhead was a catchall term for the radical, rising, dominant wing of the Democratic Party that included secret groups such as the Knights of the Golden Circle and the Sons of Liberty. Politically, the Democrats’ campaign platform for 1864 was an armistice with the South and the continuation of slavery. Directed by the Confederative Secret Service operatives, these armed mobs would use smuggled weapons and arms seized from Federal arsenals to attempt to topple local and state governments in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

Hines had reason to be optimistic about the plan’s success. Union battlefield debacles had caused unrest in the Midwest and gains for Democrats in Illinois and Indiana. “Copperheads have not uttered one loyal word, but have belched treason, day and night,” the Chicago Tribune opined. Indiana Democrats tried to strip pro-Union governor Oliver P. Morton of state troops to keep them out of the war.

These events forced Lincoln to dispatch thousands of troops to the Midwest. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts wrote to a colleague after meeting Lincoln, “These are dark hours. . . . The President tells me he now fears the ‘the fire in the rear.’”

Hines found many willing volunteer commandos from the former Confederate prisoners of war who had fled to Canada. Hines appointed twenty-three-year-old Captain John Breckinridge Castleman as his second in command. Both men were escape artists.

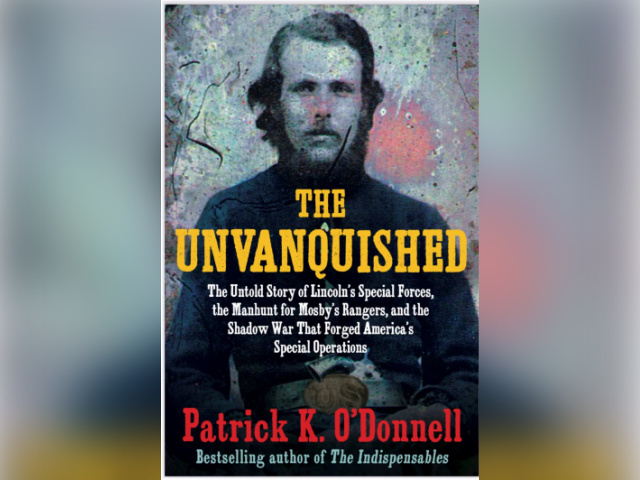

Bestselling author Patrick K. O’Donnell’s “The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations”

In 1863, the Confederate cavalry officers and many of their men were imprisoned in Ohio. They had been part of General John Hunt Morgan’s unsuccessful cavalry raid into Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio. Drawing inspiration from Victor Hugo’s descriptions of escapes through the Parisian sewer system in his famous novel Les Misérables, Hines and his men burrowed a nearly 30-ft-long tunnel. After weeks of work, they finally emerged, and they used a rope made from sheets and a grappling hook fashioned from a poker to climb over the prison wall and escape. Hines was recaptured, only to break out once again and walk into Confederate lines.

Elements within the Copperhead movement, specifically the Sons of Liberty, were primed for insurrection: “The universal feeling among its members, leaders, privates was that it was useless to hold a presidential election. Lincoln had the power and would certainly re-elect himself, and there was no hope but in force…this in sixty days would end the war.”

The radical and violent groups within the Copperheads had surreptitious signs, symbols, handshakes, and armed guards at their meetings. Over the past two years, mobs and individuals within the groups had unleashed violence, murder, sabotage, and arson: burning government warehouses and Unionists’ homes and snipping telegraph wires. Hines and Castleman hoped to harness this violence to create an insurrection.

The Democratic convention in Chicago in late August seemed like a golden opportunity to utilize the Sons of Liberty to incite an uprising and free 8,000 Confederate prisoners at nearby Camp Douglas. Hines, Castleman, and sixty Confederate commandos covertly traveled to the Windy City. But to their utter dismay, the Sons of Liberty got cold feet when the time came for the uprising. Politically, the polls tightened, and the Copperheads felt they could win at the ballot box.

Undaunted, Castleman and Hines planned round two—another insurrection at the time of the election. But Union battlefield success at Winchester, Cedar Creek, and Atlanta had altered the course of the war and, with it, hearts and minds at the ballot box had damped the ardor of many Southern-sympathizing Copperheads.

A government agent penetrated the Sons of Liberty, leading to the arrest of some of its prominent members. Hines had to pull another remarkable vanishing act as Federal detectives surrounded the Chicago house he operated from, forcing him to hide in a mattress box spring for nearly a day as they fruitlessly searched the dwelling. He escaped shortly thereafter. Spending a month on the run en route to Richmond, Hines dodged Union detectives, broke his sweetheart out of a convent, and found time to have a honeymoon in Cincinnati before returning to Richmond on December 12. Had the insurrection worked, the result could have been devasting, as one contemporary newspaper later reported: “The consequence would be that the whole character of the war would be changed, its theater would be shifted from the border to the heart of the free states.”

Efforts pioneered by Hines and Castleman live on in today’s color revolutions.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically-acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of thirteen books, including his new bestselling book on the Civil War The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations, currently in the front display of Barnes and Noble stores nationwide. O’Donnell’s other bestsellers include: The Indispensables, The Unknowns, and Washington’s Immortals. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and often speaks on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickKODonnell.com @combathistorian